For a while, it really looked as though beet juice would beat the odds. Most hot new performance-boosting supplements, even if they claim to be backed by science, don’t hold up to scrutiny. But after making an initial splash in 2009 thanks to high-profile adherents like marathon star Paula Radcliffe, the first wave of high-quality studies supported the idea that beet juice really does improve endurance.

After a decade, though, the bloom had partly faded. There were concerns about its gastrointestinal effects (much as there were with baking soda, another popular endurance-booster), questions about the appropriate dosage, and rising suspicion that beet juice only worked in untrained or recreational athletes but not in serious competitors. These days I rarely hear runners talking about beet juice, and the flow of new studies has tailed off. But a new review takes a fresh look at the accumulated evidence, and concludes that we shouldn’t be too quick to dismiss the potential benefits of the juice.

Why Beet Juice Might Help

The key ingredient in beet juice, from an endurance perspective, is nitrate. Once you eat it, bacteria in your mouth convert nitrate to nitrite. Then the acidity in your stomach helps convert the nitrite to nitric oxide. Nitric oxide plays a whole bunch of roles in the body. That includes cueing your blood vessels to dilate, or widen, delivering more oxygen to the muscles, faster.

In 2007, Swedish researchers showed that consuming nitrate—that nitric oxide precursor—makes exercise more efficient, enabling you to burn less oxygen while sustaining a given pace. Two years later, a team led by Andrew Jones at the University of Exeter found that you could get a similar effect by drinking nitrate-rich beet juice.

In subsequent years, researchers tested the effects of beet juice on various types of exercise. Crucially, Jones’s group figured out how to strip the nitrate from beet juice to create an undetectable placebo, and found that athletes improved their performance when given regular beet juice but not nitrate-free beet juice. That made the claims much more convincing. Meanwhile, a company called Beet-It began selling beet juice with standardized nitrate levels, and eventually added concentrated beet shots to make the doses more palatable.

When the International Olympic Committee put together a consensus statement on sports supplements in 2018, they included beet juice as one of just five performance-boosting supplements with solid evidence. (The others were caffeine, creatine, baking soda, and beta-alanine.)

What the New Review Found

Over the years, scientists have made numerous attempts to sum up the evidence for and against beet juice. The latest attempt, published in Sports Medicine by a group led by Eric Tsz‑Chun Poon of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, is an “umbrella review” of nitrate supplementation, mostly from beet juice. It pools the results of 20 previous reviews that themselves aggregated the data from 180 individual studies with a total of 2,672 participants.

The problem with lumping that many studies together is that they measure outcomes differently, use different dosing protocols, and have different study populations. Still, the broad conclusion is that beet juice works—at least for some outcomes. Most significantly, it improves time to exhaustion: if you’re asked to run or cycle at a given pace for as long as you can, beet juice helps you go for longer.

On the other hand, there was no statistically significant benefit for time trials, where you cover a given distance as quickly as possible. That’s the type of competition we care about in the real world, so this non-result is concerning. Time-to-exhaustion tests produce much bigger changes than time trials: a common rule of thumb is that a 15 percent change in time to exhaustion corresponds to about a one percent in a time trial. So it may simply be that the studies were too small to detect subtle improvements in time trial performance.

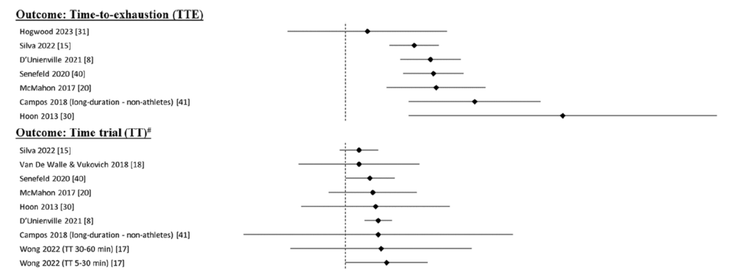

Check out the relative effect sizes for time to exhaustion and time trial in these forest plots. Each dot represents an individual study with its error bar; the farther to the right of the vertical line it is, the greater the performance boost nitrate provided.

Taking the time trial data at face value, the results still look pretty encouraging. They’re all positive; they just need more participants so that the error bars will get smaller and no longer overlap zero. Of course, eyeballing the data like that is risky because it allows us to draw whatever conclusions we want. But I find it difficult to imagine a scenario where improving your time to exhaustion doesn’t also translate into an advantage in time trials. The two tasks are different psychologically, but they both rely on the same underlying physiological toolset.

Poon and his colleagues also run some further analysis to check whether the dose makes a difference. They conclude that the effects are biggest when you take at least 6 mmoL (just under 400 grams) of nitrate per day, which happens to be almost exactly how much a single concentrated shot of beet juice contains. The effects are also maximized when you supplement for at least three consecutive days rather than just taking some on the day of a race.

What’s We Still Don’t Know

The big open question that Poon’s review doesn’t address is whether beet juice works in highly trained athletes. Several studies have found that the effect is either diminished or eliminated entirely in elite subjects. This isn’t surprising. Pretty much every intervention you can think of, including training itself, will have a smaller effect on people who are already well-trained. This ceiling effect is presumably because elite athletes have already optimized their physiology so thoroughly that there’s less room to improve.

The flip side of that coin is that, for elite athletes, even minuscule improvements can be the difference between victory and defeat. The size of a worthwhile improvement at the highest level is a fraction of a percent, which is all but impossible to reliably detect in typical sports science studies. For top athletes, the decision of whether or not to use beet juice will have to remain an educated guess for now.

There are other unanswered questions, like whether beet juice is better than consuming nitrate straight. There have been several studies suggesting that this is indeed the case. The theory is that other ingredients in beet juice, like polyphenols—which function as antioxidants—might act synergistically with nitrate to produce a bigger effect. But as another review pointed out last year, the evidence for this claim is too shaky to draw any reliable conclusions either way.

Probably the biggest risk in the beet juice data is the preponderance of small studies, some with fewer than ten subjects. It’s easy to get a fluke result with small sample sizes, and it’s human nature to get unduly excited about positive results—which is why positive flukes often get published more often than negative flukes. So we should remain cautious about our level of certainty.

Despite that caveat, my overall impression is positive. I sent the following summary to Andy Jones, the scientist most associated with beet juice research, to see whether he would agree:

“It works. It probably works less well in elites, like most things, but there may still be an effect. Higher doses taken for at least a few days in a row probably increase your chances of a positive effect.”

Jones thought that sounded reasonable. He pointed out that there’s a separate body of evidence emerging that beet juice also enhances muscle strength and power in some circumstances, an effect that Poon’s review confirms. For endurance specifically, looking at the totality of evidence, Jones figures there’s a real effect. And he’s in good company. “Eliud remains a big believer,” he pointed out. That would be Eliud Kipchoge.

***

For more Sweat Science, join me on Threads and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my new book The Explorer’s Gene: Why We Seek Big Challenges, New Flavors, and the Blank Spots on the Map.